How do I ~ PB A Hill?

when one hill isn't enough...

James Falshaw enjoying the incredible

Nove Colli

Climbing is within us all. Not everyone likes climbs, but we all like a challenge, that's why we ride, race or do sportives.

You may not be able to be the fastest climber in your town, team, or for some house, but almost every one of us can climb better and grab a PB this coming season. Well here's how you can, it's simpler than you think.

As ever, it's all about being smarter, not stronger or harder.

Gather

Data

Gather

Data

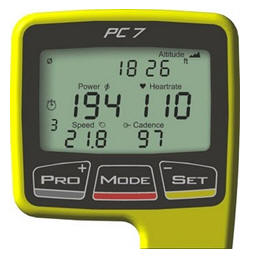

First you need to find a local challenge. Then you need the

tools and a strategy to tackle it.

I'll deal here with using a power meter, as it makes it dead easy to get the concept across.

But you don't need these fancy gizmos. All you need is a bog standard cycle computer that has a speedo and a stopwatch.

Transfer the principles to your own situation and you have almost guaranteed success and the first of many season's PB's

Once you have mastered "the system", you just continue to replicate it to repeat your new found successes. The only limiters are your physiological capabilities and current fitness condition.

Is He Moaning Again...?

A coach has three main tasks. The first is to help an athlete

to realize their potential; the second is to protect the athlete's

welfare and safety while meeting task one; and the third is to get them to do things they

don't like doing, or would not choose to do if left to their own

devices.

But in reality I spend most of my time moaning. Racers like to ride fast, anaerobic and erratic, coaches like to ride slow, aerobic and steady. I spend half our team rides screaming "Steady, Steady, Steady". We really should get team radios...

For me, it's constructive advice to help meet tasks one and three above. To riders, because I'm stopping them doing what they like doing best (going fast), it's moaning!

But for this task of hitting a climbing PB, your first objective is to ride up your climb of choice, as fast as you possibly can. If you can't taste a little bit of sick in your mouth at the end, you haven't done it right.

Pick a local climb (initially anything from three to ten minutes will do) that is relatively straight, quiet, free from traffic and unaffected by climatic conditions (wind). Try to choose a steady, five-percentish, climb that has a nice and as constant a slope as possible.

Your first attempt will be a do or die effort. Just try not to die otherwise we won't be able to continue on to step two...

flamme

rouge team assault on the legendary

cobbled Muur de

Gerardsbergen

Susan Clark, Pete Slattery & Simon Perchard ~ having a near death experience

Hold Nothing Back

For your first effort, you are trying to establish a power

average for the complete climb. Obviously you have to make it to the

top, but your effort will probably follow the spectacularly classic

"decaying wattage" pattern of most "amateur" riders

that climb climbs.

It will probably (I can guarantee) look something like this. Which is an actual power profile of a "normal", but good, rider attacking one of our classic local climbs. The mighty Rozel (Roe-zell); at around five minutes and 92 metres, it's our island's longest and highest climb!

The fact that we had a pro riding with us on the same day has nothing to do with the outcome of this desperate situation. It would have happened like this anyway...

amateur rider power profile (yellow) for a five minute climb

This is how I expect yours (or any other non-pro rider's profile) to look when tasked with getting up a climb as quickly as possible.

Most riders use this strategy for every hill they come to. Always have, always will. It's this habit that we need to break.

Our rider starts by hitting the climb at 425 watts, rapidly pushing up to 450 -500 watts just before the inevitable oxygen debt begins to kick in.

The irony of the fact that it was this rapid rise in effort that caused the oxygen debt is (and always will be) overlooked by our intrepid grimpeur.

The lack of available oxygen means power falls, heart rate climbs, lactate develops. People (the pro amongst others) start coming past in ever increasing numbers; which "obviously" ignites our rider's testosterone-fuelled competitive response. Or as we coaches call it; "panic".

A gear change ensues and the "dead man's kick" strategy is pulled in to play. We are now heading for the globally seen phenomenon of cycling's equivalent to a Malthusian Catastrophe.

This doomed neuro-muscular response lasts about ten seconds (you can clearly see it in the middle of the chart) before ATP runs out and the slow, embarrassing, bike-wrestling, panting grind to the summit begins.

The crest is approached at 200-250 watts and dropping. Lactate is lapping around the ears, squares are being pedalled and words are being had. At the summit, our rider is in no fit state to push on, should an attack take place. Which, on a race day, it almost certainly will.

It matters not what the numbers are. I see hundreds of climbing power files a month and in the early days, they all look exactly like the above.

It's the shape that interests me, not the number. This is a shape, and a pattern of behaviour, with which I have become very, very familiar.

Dr Andrew Kelly

clearing mighty Ventoux in the Haute Route

absolutely not using the technique described above

What now?

Well, we've gone out and ticked the data gathering box. Now we

move to "step two" and turn it in to

information.

Information in context leads to knowledge, and knowledge, as we all know, is power. Which co-incidentally is our first starting point; power.

Let's just stick with the wattage numbers we have to keep it simple. But obviously, you transfer these principles to your situation, on your climb, with your numbers.

You can see that the above rider peaked at 500 watts and dropped to 200. Now there is no way they could hold 500 watts for five minutes. But they could easily hold 200 watts for five minutes.

Commonsense tells us that somewhere between those two numbers is their ideal climbing wattage.

Looking at the data from the climb (using Strava or WKO etc), we can see that our rider averaged a solid 300 watts for this climb. So guess what step three is?

Yep, we take a few days recovery, sort ourselves out, promise to keep everything in check, then head back to the climb...

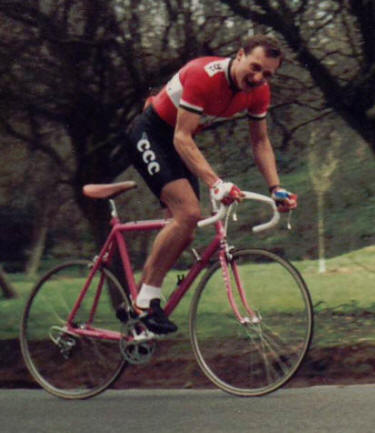

Guernsey Easter Festival 1987 Val de Terres Hill

Climb Stage

Me ~ no gizmos, trying not to be sick; but I so very was at the top!

Black, lace up shoes, white socks, 7 downshifter gears, 32 spokes,

3" seat post.

Steady, Steady, Steady...

As you approach the climb, the only number you

should have in your head is

your previous, "optimistic" attempt's average wattage (or speed).

For our purposes, this is 300 watts. For the first minute of the climb, you sit at 280-290 watts, which is just under your average output.

Eventually, the heart rate, lactate and perceived effort feedback systems will catch up. You will then have a good sense of where you are and how hard you think you can crack on. It matters not.

Whatever you do, do not go above your average wattage for the climb, in our case 300-310 watts. This is crucial to your understanding of how your body works.

Just tap it out and keep calm. Even though you can see the top of the climb, and you know you can light it up, just hold that level of effort until you top the crest. This isn't your day to PB! This is the day you change the way you climb forever.

The first thing you will notice is how undramatic, and slow, the first part of the climb seems. The middle has an air of mediocrity about it, which is unsurprising as we're riding it at a median output. Even the finale is a little anti-climatic. All in all, nothing to get excited about.

But then you realise, you're hardly breathing (too heavily), your heart rate is five to ten beats down on your previous attempt and you could, if you wanted, or had to, have sprinted the crest!

You do your other riding stuff, go home, load up your data and look for your segment time. You are within seconds of your data gathering attempt, without even trying. How good is that? Same time, same power average, less effort, less stress, less drama.

Now. Armed with a new climbing strategy and new found

self-confidence, it's time to go back smash the living daylights out

of it. Or is it?

Mark Hall ~ Smashing

the Trois Ballons

and making it look simple...

Whoa Steady The Bus...

To quote the great David Duffield! Now we're going to sort

this climb out in just three rides, all of which have the potential

to be PB's. So pay attention, because this is the bit that

could change you in to a climber.

Okay, we've been back and ridden our climb at our average wattage and found it "easy". It's a relative term.

Now we go back and ride the climb with a slightly different approach. We're now going to break the climb in to three distinct parts. Starting, surprisingly, with the last third.

Hit and hold the climb at your average wattage for the first two thirds. In our case, it's 300 watts for three and a half minutes; easy.

We've proved we can hold this for five minutes, so this should be a doddle. Once we get to that marker, we have one and a half minutes left to the crest. Perhaps we can hold 375 watts for that length of time? You know you'll blow at 400+ watts, so don't go there.

Give it a go and see what happens. Whatever you do, you'll probably make it without floundering and set a PB for the climb. At the very worst, it'll be within seconds of our first attempt.

Ride two, is exactly the same concept as the first. Hit it at your default wattage/effort/speed, hold it for the first third, then open it up for the remaining two-thirds.

In our case we could say, 300 watts, first third, 330 watts second third, 360 watts last third. You'll notice the last third is less than it was on the second run, as we ate in to our reserves a little when we clocked 330 w for the middle stint.

But what you'll now notice, is that our average for the whole climb is 330 watts. Ten percent higher than our original baseline effort; and it will still feel easier than the first. All this is in just a few rides!

Paris Roubaix Winner Magnus

Backstredt getting some Spring Classic prep in!

The pro wasn't him by the way; it was one of his riders.

Climb Like A Pro

Looking at the pro's power profile, we can see they have a much

greater sense of awareness of how their body works. He never

looked at his computer once on the climb, this was ridden on feel.

how a pro rode the same climb on the same day on the same ride

The pro's climb consisted of three thirds, as do all climbs. They eased in to the first third of their attempt at 350-375 watts. Probably within the realms of a good club rider.

They gently took it up to the 400+ mark for a bit, sensed they were flirting with oxygen debt (they'd already destroyed the rest of us), so dropped the last third back to the upper edge of their initial effort, at 375 watts.

All in all, they averaged 385 watts for the climb. Which is 85 watts higher than our "normal" rider. On paper, it looks like our normal rider is only 28% behind our pro rider. But as I'm always saying, power numbers mean nothing unless placed in context.

Our normal rider, put out 300 watts at 75 kilos, which is bang on 4 w/kg. Our pro rider put out 385 watts at 67 kilos, or 5.74 watts per kilo. And to be honest, they weren't really trying!

To save you doing the maths, our pro is 43.5% more powerful on our demonstration climb. Now that's impressive...

New Baselines & Boundaries

Within a very short time we've reset our

baseline parameters. Not only

are we climbing faster, we've induced less physiological stress in

doing so.

What we are training here is our mind and our ego.

We haven't increased our output spectacularly over the three weeks it's taken to do this routine. We've made better use of what we have.

And the fact that we've made ourselves more efficient, means we have more energy and physiological resources left over to make ourselves more effective in the coming weeks.

Combine the two, and very, very quickly you've got "leaps and bounds improvements". Thrashing around on a climb isn't the way to improve one's times or technique.

if you want impressive, wait until you hear

about this

Bracken Spencer ~ Utah Hill Climb

Champs

To show what discipline and controlled effort can bring, check out Bracken Spencer above. He's a big lad, with a big accomplishment.

Bracken, at 100 kilos, won Montana's State Hill Climb Championship, on the 40 km climb of Beartooth Pass, in 1:49:56:00. This climb FINISHES at 3287 metres, and starts at 1600 metres. On the day it was freezing rain in places, with the temperature at 34 degrees Fahrenheit (1.1 C).

Bracken powered up this "high altitude, low oxygen density", freezing climb holding 331 watts for an hour and three-quarters. I'll let you think about that for a while...

The Message

Climbing is a skill that can be learnt. It's not all about

brute force.

Some are more adept to climbing than others, having the right genetic disposition and having the foresight to have chosen the right parents.

Muscle size has nothing to do with climbing, it's muscle content. Fibre type, muscle capillarization, lung capacity, oxygen uptake, oxygen saturation, cardio output, plasma levels mitochondria, etc, etc, etc.

So stay out of the gym! Because body size is a negative contributing factor. For every kilo you can lose, while keeping the same power, you will climb 2.75% faster. And muscle is heavier than fat.

Look at Froome's legs, they're like our arms! You don't need big legs to climb, you need big lungs.

It's far easier to lose weight than it is to gain power, so why not consider that option first. Add that to your new found climbing technique and how can you not rack up PB's come the spring and in to the summer?

Do the right things, in the right order, and you can get the right results...

Kat Guillemot ~

showing the boys how it's done on the

German Road

The finishing climb of the Mont Cambrai Road Race

Have fun and suffer well, if just a little more controlled than usual...